A tutorial on Antic modes 4 and 5

Most owners have heard of Atari's ability to

re-define characters even if they are not sure how it is done.

Character graphics are a quick, versatile and memory efficient way of

developing game playfields and simple animation. In this article I

will show you how to use two of the least understood of the text or

character modes.

One problem with using character graphics is that

the best looking characters are only available in Graphics 0, which

only allows one colour. In Graphics 1, characters can be any one of

four colours, but the loss of resolution makes them look rather

chunky. What would be most useful would be a graphics mode with the

resolution of Graphics 0 but with more than one colour available,

preferably without using extra memory. It would be even better if the

characters themselves could be made up of more than one colour. Well,

believe it or not just such a mode is available on the Atari. It is

known as Antic 4 or on the XL and XE machines as Graphics 12. Antic 5

(Graphics 13) is a similar mode but with less resolution. These modes

are used extensively in commercial games, but for some reason tend to

be less used by the ordinary Atari user. I suspect that this is partly

due to lack of awareness of the existence of these modes and partly

due to the need for a little extra programming in order to use them.

Why Antic 4 and 5? As many of you know, Antic is the

chip inside the Atari directly responsible for producing the display

on the TV screen. It recognises 14 different graphics modes (numbered

2-15 by Antic) plus the three GTIA modes, but unfortunately not all of

these modes are directly available from BASIC, at least in the

400/800. I understand that all but one of these modes can be called

from BASIC in the XL models, however all the programs in this article

should work equally well on both XL, XE and older machines. Antic 4

and 5 can therefore be termed as two of the `hidden' modes The other

three are Antic 3, 12, and 14 and would perhaps be a suitable subject

for another article.

How then do we get into these modes? Antic is told

how to display data on the screen by means of a set of instructions

called the Display List. This isn't intended to be an article on

display lists as such (yet another article!) so suffice it to say that

to use Antic 4 or 5 we must either set up our own Display List or

modify an existing one. (XL or XE users can simply use a Graphics 12

or 13 statement).

Antic 4 is similar to Graphics 0 in screen format

and memory requirement so to use it we merely change the existing

Display List. We can find the start of the list easily enough by

PEEKing memory locations 560 and 561.

Listing 1

|

|

|

|

Listing 2

|

|

|

|

Listing 3

|

|

|

|

Without

further ado therefore, type in and run Listing 1.

Notice that

the default background colour to Antic 4 is black. Notice also that

you can't read the characters! Why this should be so we will discuss

later. In all other respects Antic 4 is treated as Graphics 0 by the

Operating System and all of the screen editing and cursor control

features will work normally. You will stay in this mode until you do

another Graphics call or press System Reset.

Antic 5 is a little more difficult The problem is that there is no

other mode available with equivalent resolution. Graphics 1 has 20 x

20 resolution giving double width characters, plus a text window,

while Graphics 2 has 20 x 10 resolution giving double width, double

height characters. Antic 5 however has 40 x 10 resolution (normal

width, double height characters), assuming a text window is added. The

easiest solution is to construct your own Display List and place it in

a protected area of memory such as page six. To do this, type in and

run Listing 2.

A brief word

concerning this program may be helpful. Line 10 reads the data for the

new Display List and POKES it into page six of memory. The only data

we don't have is the starting location of screen memory and of the

text window memory, and this is represented by the zeroes in line 100.

Graphics 1 needs the same amount of memory as Antic 5 (even though the

screen format is different) and calling Graphics 1 in line 20

automatically allocates the correct amount of RAM. Locations 88 and 89

point to the start of screen RAM and 660 and 661 point to the start of

text window memory. The values in these locations are then POKEd into

the appropriate places on page six. Line 30 redirects the Display List

pointer to our new list. One further problem is that although we know

that 40 characters can be printed per row, the Operating System thinks

it is in Graphics 1 (from line 20) and will only allow 20 characters

to be printed per line. We can trick the computer into thinking it is

in Graphics 0 (40 characters per row) by POKEing 87 with zero, which

allows us to use this mode fully. Having opened channel 6 to the

screen by the Graphics call in line 20, we must use this channel to

print onto the Antic 5 part of the screen. One final snag to watch for

here - only 10 rows are available for printing (not counting the text

window) but the OS, thinking it is in Graphics 0, will allow you to

print up to 24 rows without returning Error 141 - cursor out of range.

Attempting to print outside of this 10 row limit may cause

interference with the OS RAM below screen memory, causing a program

crash.

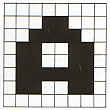

Let us return to why the text is not readable in these two modes. As

you know Atari characters are constructed on a grid of 8 x 8 pixels.

Each pixel can either be 'on' or 'off' (i.e. lit or unlit), so that

the letter 'A' for example would be made up like this:

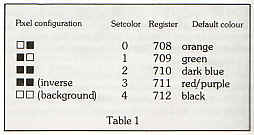

In Antic 4/5 however, each character is constructed on a 4 x 8 grid,

with each pixel being twice as wide as a Graphics 0 pixel

(technically, one colour clock wide). Either half of the pixel may be

lit independently of the other, so that the pixel may also determine

colour. The pixel configurations and the colour registers used are

shown in Table 1.

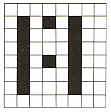

Using this chart, you should be able to define your characters in any

desired colour or combination of colours. If you look at the above

diagram of 'A' in this light, you will see that although retaining the

shape of the letter, the character is in a mixture of different

colours, making it difficult to read. Antic 4/5 characters must be

designed to take this into account. The letter 'A' in Antic 4/5,

Setcolor 0, should look like this for example:

In order to use other colour registers it would of course be necessary

to define the letter in a different fashion.

One problem with re-defining characters is that they will no longer be

readable in Graphics 0. This is unfortunate if your programs use

on-screen prompts or user inputs that you want to be readable.

However, we can change the characters back to the original set in

mid-screen by using a Display List Interrupt. Listing 3 is an example

of character re-definition and a Display List Interrupt to set up

Antic 4 with four lines of Graphics 0 at the bottom of the screen. It

re-defines the characters A, a, and Control-A as upper case 'A' in

three colours, and then prints them and their inverse video

counterparts to the Antic 4 screen. It also prints them to the

Graphics 0 window to show the use of the DLL.

The DLI also restores the default background, border, and character

luminance colours so that you can alter the colour registers as much

as you like without making the text unreadable. The DLI itself and the

machine code routine to move the old character set into RAM are kept

as separate subroutines for use in your own programs.

Note that the screen does not have a true text window. Anything

printed here will normally scroll into the rest of the screen with

further inputs or prompts but line 100 prevents this. To see the

effect, press BREAK and then RETURN several times.

Listing 4

|

|

|

|

Listing 5

|

|

|

|

The program

will need to be changed for Antic 5. Substitute the lines in Listing 4

for their counterparts in Listing 3.

Two points

to note. Firstly, the characters don't look as good as they do in

Graphics 0, because we are defining them with less resolution (4 x 8

as opposed to 8 x 8 pixels). Secondly, note the curious way in which

inverse video is treated. Those pixels used with only one half of the

pixel lit are unaffected, but those with both halves lit (using

Setcolor 2) change colour (to Setcolor 3) in inverse video. This gives

us four colours on screen, but only three in any one character.

So far, I have made no mention of the best feature of these modes -

the ability to use characters consisting of up to three colours. For a

brief example, substitute the lines in Listing 5 for their

counterparts in Listing 3. You should see each letter 'A' appear in

two colours.

I appreciate that 'A' in two colours is not the most exciting thing

you've ever seen, but bear with me a moment. Of course, if you want

full multicolour text on your Atari, you will have to redesign all the

characters. I will leave this for you, but note two things. Firstly,

you will lose some of your character set - whichever you choose to

redesign. In the above example, we lost the lower case and Control-A

characters. Secondly, design is greatly helped by a character

generator utility which supports Antic 4/5, my own personal favourite

is 'Magic Window' from Quicksilva. The best of the public-domain

programs is probably 'Create-a-Font' published in Analog magazine

(February 1984 issue). Compute! magazine published a very useful

utility called 'Antic Aerobics' in October 1983 specifically for the

creation of pictures using groups of multicoloured characters.

Listing 6

|

|

|

|

Listing 6 is a subroutine intended for insertion into Listing 3 above.

The characters were created with 'Antic Aerobics' and if you can be

bothered to type in all that data you will get a better idea of

exactly what can be achieved in these modes.

Not only do Antic modes 4 and 5 allow you to create superb displays

they give you the versatility of character graphics (including

animation) and considerable memory savings. Consider for example that

whilst Antic 5 pixels are the same size as those in Graphics 7, Antic

5 requires only 0.5K memory while Graphics 7 uses nearly 4K.

I hope this article has started you thinking about the 'hidden' Atari

graphics modes and I look forward to seeing more programs appear in

PAGE 6 using them.

top